How being donor-conceived affects you growing up

Two donor-conceived women share how their status affected them growing up, and a therapist gives advice on to how to deal with a teenager shouting “You are not my real dad”.

When Nete, a young donor-conceived adult, was a child it didn’t matter much to her, that she wasn’t biologically linked to her father. She mostly thought that it was cool that she had been frozen before being born.

“I don’t mind being donor-conceived. It’s not that it’s a bad thing at all and I haven’t suffered in any way,” she says.

I do wish I knew something about my donor.

But she did often look at strangers, searching their faces for similarities. She was curious about who the donor was, but she was afraid of hurting her father if she shared that curiosity with him. When she finally did, he was very understanding.

Nete is conceived with the help of a No ID release donor, which means that she has no identifying information about him. When she was 12, she heard a radio news segment discussing what was then called open donors and the possibility for children to learn their donor’s identity.

“I remember feeling angry. I didn’t have words for it at the time, but I think I was jealous because I realised I wanted to have the opportunity to know where I came from.”

“I do wish I knew something about my donor. And I’m critical of the fact that it’s not up to the donor-conceived person to have that information,” she says.

Listen to episode 4 of ‘Being donor-conceived’ here:

“You are not my real father”

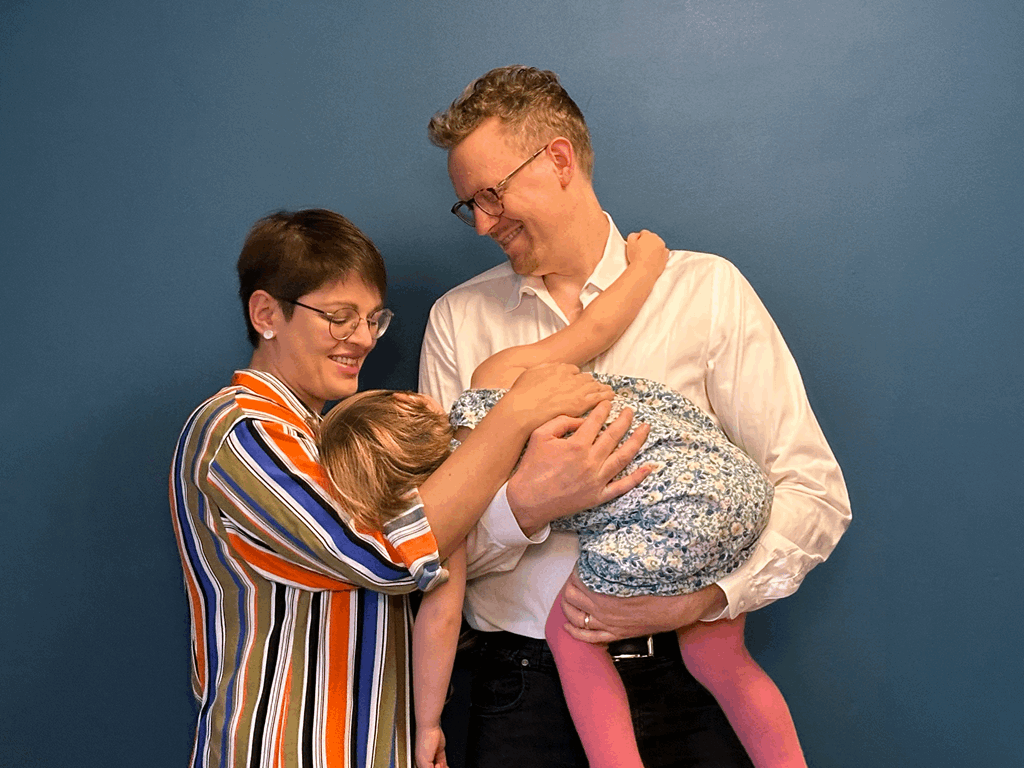

Before becoming a father, Kristoffer Vitting-Seerup used to worry a lot about, how his donor-conceived daughter would feel about him. They don’t share DNA due to Kristoffer’s infertility. What if she would shout that he is not her real father as a part of a teenage rebellion?

“I would have nightmares about that. It would be the most horrible thing I could imagine. I was very insecure in my role as a parent. But that has changed now that I have Meta. There is no doubt in my heart that I am her father no matter what she does or what she says. And throwing a teenage tantrum won’t change that,” he says.

Read Kristoffer’s full story here.

Psychotherapist Lise Kramer, who specialises in donor-conceived families, says that situation will most likely occur.

“The teenage years are full of rebellion and separation themes whether the child is donor-conceived or not. So, the child will probably say that you are not my father,” she says.

She advises parents to keep calm.

“Simply say yes, you are my child,” she recommends.

Biology doesn’t make a parent

Lærke is a donor-conceived young woman, who learned that she was not biologically linked to her father when she was 11 years old. That fuelled difficult emotions during her teenage years.

Her parents divorced when she was young, and she grew to be quite close with her stepfather.

“I had a more complicated relationship with my father, and I think I used the lack of a biological connection to explain our differences. As a teenager, I distanced myself from him,” she says.

Her father has passed away, and her complex relationship with her father affected her grief.

“His role in my life wasn’t very clear. Who is this person that I lost? What constitutes a father? Who is my father, and who is my stepfather, what are their roles?” she says of the thoughts she wrestled with.

Looking back, she has one advice she would have liked to give her teenage self:

“Don’t let the lack of biological connection be the reason to distance yourself from a parent.”

“Parents are parents not because of their biological material, but because of their actions, their care and their decision to become parents,” Lærke says.

This blog post is based on episode 4 of the podcast ‘Being donor-conceived – Stories from children and parents’.

Lotte Sørensen

Lotte Sørensen